Bruno De Wachter, Independent Advisor, International Copper Association

Since the publication of the EU Green Deal, e-mobility OEMs and Tier 1 suppliers in Europe have been actively seeking ways to evolve towards carbon neutrality. For such a journey to be successful, open communication across the entire value chain is essential. This article develops the case for copper, a key raw material of the EV powertrain.

Copper in EVs – There is great potential to significantly reduce embedded GHG emissions associated with copper in the years to come.

Copper has the highest electrical conductivity of all non-precious metals, a quality put to good use in the stator windings of electric motors and induction motor rotors, as well as batteries, cabling and electrical connections. As OEMs and Tier 1 automotive industry suppliers develop their decarbonization plans, reducing copper’s embedded greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is one of the challenges. A common approach to achieving this is by setting out a series of KPIs and milestones for their copper suppliers.

The good news is that there is certainly potential for reducing the carbon emissions from copper production to net-zero over the coming 30 years, and without the need for major technological breakthroughs. But for these conditions imposed by manufacturers in the automotive industry to be effective and actually help the copper industry speed up their decarbonization process, they have to be formulated in the right way, which requires some insight into the copper production process and material flows.

The copper production process and its emissions

A whole sequence of processing steps is required to produce high purity copper. The process of extracting primary copper from ores begins, of course, with mining, followed by concentration through a flotation process, and a first stage of refining in smelters using pyrometallurgical methods. The material is then subjected to a second stage of refining through electrolysis. An alternative route for low grade ore is the hydrometallurgical process, which separates the copper from the ore through leaching and then extracts it from the remaining solution through electrowinning.

Secondary copper is produced from scrap originating from manufacturing processes or end-of-life products. High purity scrap can be remelted directly with no need for refining, while less pure scrap requires additional processing. This can take place in dedicated secondary smelters, or the material can be added to the primary production process at various stages, depending on the scrap’s purity. This means that high-quality copper metal is often produced from a combination of primary and secondary sources.

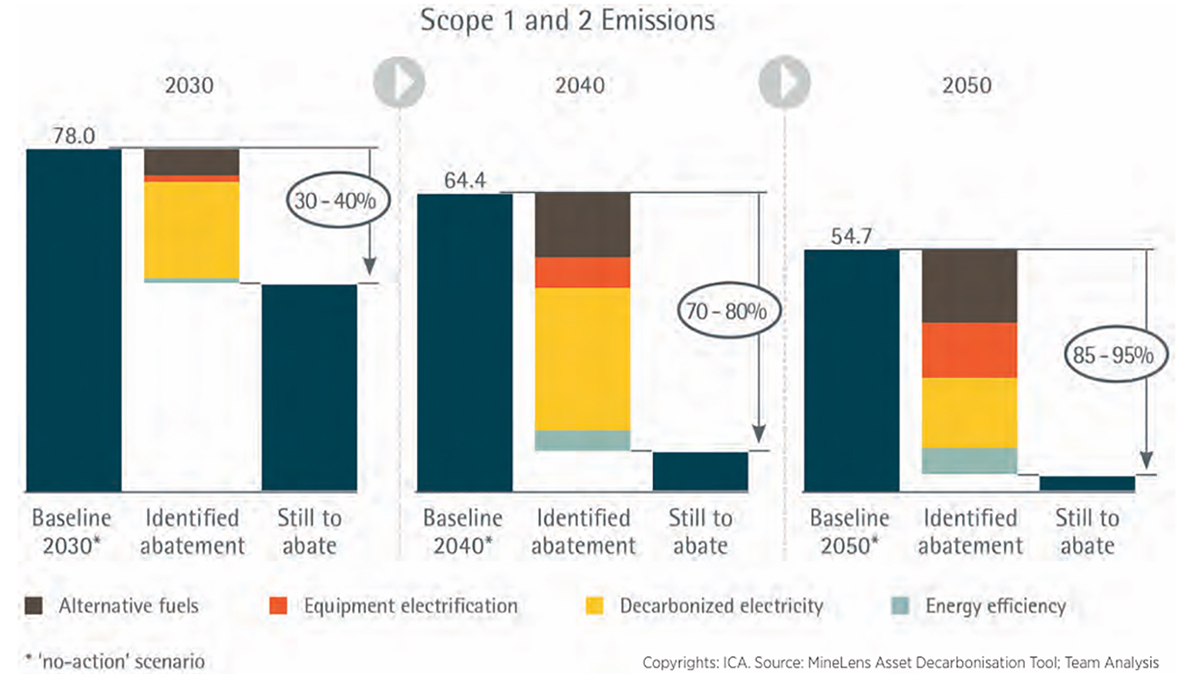

According to an analysis by the International Copper Association (ICA), copper production currently leads to a total of 97 million tonnes of GHG emissions annually, or 0.2% of total global emissions. Of these emissions, approximately 70% are generated by mining, 23% originate from smelting and refining, and the remaining 7% come from upstream and downstream transport and end-of-life treatment of products.

A major component of the GHG emissions associated with primary copper comes from electricity, from fossil fuels used in mining transport and equipment, and from fuels used in smelting furnaces at various stages of the production process. The GHG emissions of secondary copper depend on the purity of the scrap, since this determines at what stage in the refining process it is added, but they are generally lower than those from primary copper. That said, using secondary copper can never be the sole and complete solution to decarbonization, as explained later. For this reason, reducing the impact of the primary production routes should receive major focus in the decarbonization process.

The pathway to net-zero

The decarbonization of the copper production process has already started, with numerous initiatives by individual companies involved in copper mining and refining. To step up the momentum, the ICA with its members developed a path forward to bring the carbon foot print of copper production as close as possible to net zero by 2050 (’Copper – The Pathway to Net Zero’). Made public in March 2023, the Pathway sets out a pragmatic approach to decarbonizing copper production, using existing technologies. It delineates which decarbonization options can be activated, by when, and with what impact. It also outlines some enabling conditions that should be in place to achieve this.

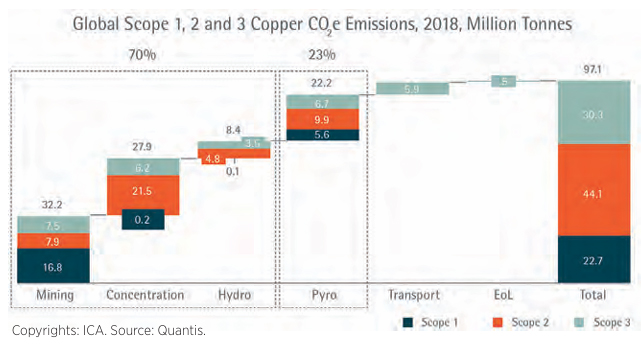

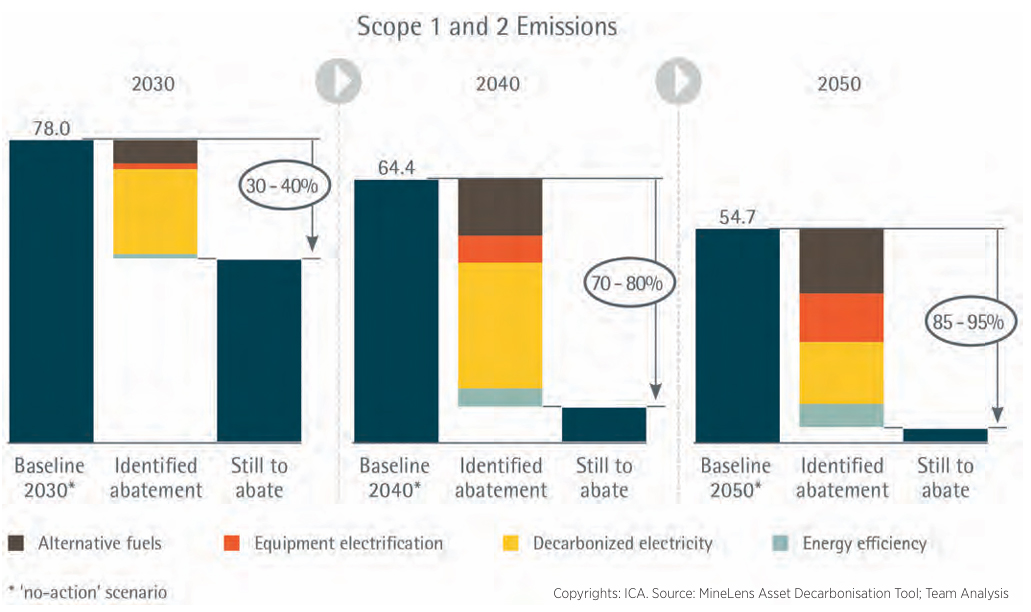

For scope 1 and scope 2 emissions, the Pathway identifies four major types of levers. The first is equipment electrification, to include the haulage trucks used in mining. An example of good practice is demonstrated by Boliden, a Swedish mining company which introduced electric trolley assistance in its haulage trucks in 2018, saving significant amounts of diesel fuel (Boliden, 2018). At the same time, underground mining machinery is being electrified at a rapid pace, coming with the additional benefit of saving the energy and cost of ventilation. The second lever is decarbonizing the electricity supply. This includes switching from standard to green electricity, alongside the option of installing wind and solar energy farms at copper production sites. A third lever is replacing fossil fuels with biofuel, biogas, or green hydrogen, particularly in smelting furnaces. A fine example of this is at German copper producer Aurubis, which has started using hydrogen instead of natural gas for the reduction process in its anode furnaces – an innovation set to reduce GHG emissions by around 5,000 tonnes each year (Aurubis, 2023). The fourth major lever encompasses various kinds of energy efficiency improvements at various stages of the production process. In a collective commitment, ICA members declared that they will be applying these and other measures to reduce their scope 1 and 2 emissions by 30 to 40% by 2030, 70 to 80% by 2040, and 85 to 95% by 2050.

A similar approach has been followed for scope 3 emissions, subject to the proviso that the results for this category depend on all the actors in the value chain collaborating. ICA members aim to reduce these emissions as far as possible by 2050, and will do what they can to unite every stakeholder behind this goal.

Recycling and decarbonization

Copper’s infinite recyclability is a major advantage. About 80 percent of copper is used in an unalloyed form, making the recycling process more straightforward. Even for copper that is alloyed or contains other materials, recycling can still be achieved without downgrading. Unwanted elements can be efficiently removed to recover the copper in its pure state, ready to be re-used in any kind of application. Because of its high degree of recyclability, copper already in use in its various applications is not regarded as lost, but can instead be legitimately considered part of the world’s copper reserve, often referred to as society’s „urban mine”.

Its high level of recyclability, combined with the fact that copper from secondary sources produces fewer GHG emissions than primary sourced copper, could lead to the simplistic conclusion that increasing the share of secondary material would be a good strategy for reducing embedded emissions. While this solution will work at individual plant level, it does not make sense on a European or world wide scale. Due to the long average lifetime of products using copper (typically 25 to 30 years) and strong growth in copper demand (practically doubling every 30 years), the availability of end-of-life material is far too limited to meet the demand for new material. Additionally, no process is 100% efficient, and there will always be losses associated with collecting, separating, and re-processing copper scrap.

Note that a distinction should be made between fabrication scrap, which originates from the production of end-use material out of semi-finished goods, and end-of-life scrap, which originates from end-of-life products.

Globally, scrap recycling rates from end-of-life products averaged around just 15% over the period from 2000 to 2020. Estimating future recycling rates is complicated by various uncertainties, but MineSpans by McKinsey expects the end-of-life recycling input rate to increase to 23 percent over the next 30 years.

Fabrication scrap contributed to about 16% of semi-finished goods production globally, a figure expected to remain stable. Bearing this in mind, any requirement set by raw material purchasers to increase the total recycled content of new copper above 35%-40% can only result in less recycled material being used elsewhere, leading to zero net reduction in GHG emissions at global level.

Moreover, the main levers for increasing recycling rates are in the collection and separation of end-of-life material, and consequently not in the hands of copper producing companies. Design engineers at every level of the automotive industry can play their role by favouring product designs that facilitate dismantling and separation at end-of-life (“design for recycling”). In some cases, collaborations between various stakeholders and the copper industry to capture and process the cleanest scrap and create a closed loop can set a good example. Recycling rates could also benefit from incentives for end-of-life collection, from staff upskilling for end-of-life management, and from improved separation techniques for treating multi metal scrap streams. Improved systems for car registration and waste stream reporting could avoid end-of-life vehicles being exported from the EU or going under the radar in other ways.

Collaboration across the value chain

All this considered, e-mobility OEMs and Tier 1 suppliers should not be over-concerned about the feasibility of reducing the embedded GHG emissions of copper conductors. The ICA and its members have developed a decarbonization pathway for the next 30 years based on existing technologies and that will bring the carbon footprint of copper production as close as possible to net zero by 2050. But to unlock its full potential, the pathway depends on stakeholder across the value chain communicating and collaborating with each other, upstream from copper production as well as downstream.

Purchase managers from the automotive industry can work with their copper suppliers to develop a roadmap to reduce embedded emissions and offer collaboration avenues to accelerate the process.

Raw material sourcing managers responsible for purchasing copper products should be aware of the limits of using recycled content as a means of reducing embedded GHG emissions. At the same time, they could consider developing closed loop business models for copper used in the automotive industry. Design engineers can play their role in this process by facilitating dismantling and separation at end-of-life.

With this level of collaboration across the entire value chain – stake holders communicating and interacting and achieving what is within their reach – there is great potential to significantly reduce embedded GHG emissions associated with copper in the years to come, while improving the collection and recovery rates of copper in end-of-life vehicles.