The new 8DCL900 is more than just a highlight in supercar transmission development. As our interview with Dr Jörg Gindele shows, taking technology to the limits can benefit large-scale production too.

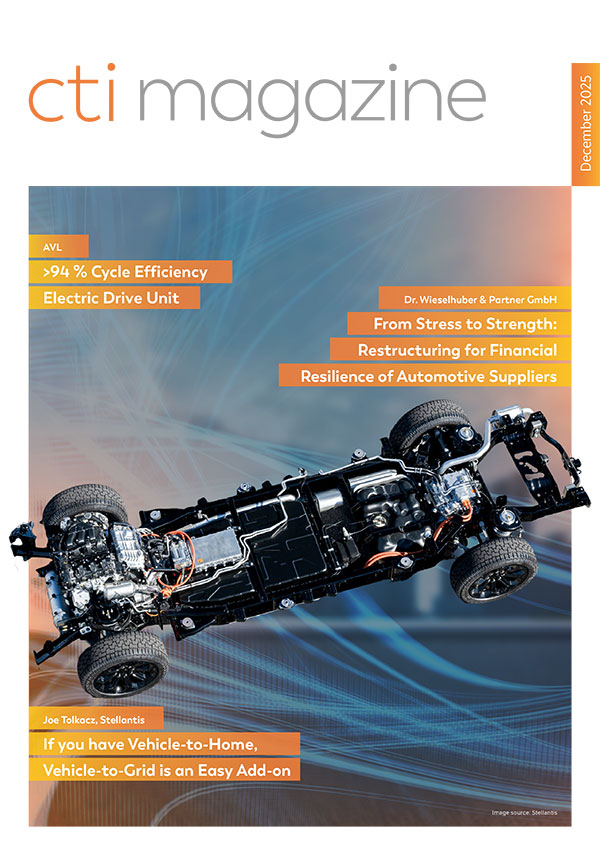

Mr Gindele, the new 8DCL900 Performance Dual Clutch Transmission you and Ferrari co-presented at CTI Berlin has a proven predecessor: the 7DCL750. Why the new development?

Performance cars have extreme torque and performance requirements. These have increased significantly in the past ten years, one reason being hybridisation. For example, the Ferrari SF 90 Stradale has an e-motor between the engine and transmission that enables overall peak torque ratings of up to 1100 Nm. We also wanted to significantly improve shift times – and direct hydraulic control has clear advantages there. On top of more performance, we also wanted even more internal efficiency. The additional eighth gear improves overall efficiency too. And finally, we wanted to get the car’s centre of gravity even lower. So to achieve a lower installation position, we moved the whole hydraulic system up within the transmission. A transmission like this is also a reference product.

What insights can you transfer to series production?

That’s an important point. We often ask ourselves what we can adopt from racing or high-performance applications that let you explore the limits, and demand that you do. For instance, we developed a new transmission casing with a honeycomb structure that’s lighter, and improves casting quality even more. We’re now adopting the new method in all series-production applications. Other examples include high-end triple carbon synchronizers, plus new materials and tooth geometries. Asymmetrical toothing is important because you can put more torque on the traction flank than on the thrust flank. We’re transferring that to series production too. You mentioned hybridisation in sports cars.

How does that differ from large-series production?

Performance hybrids and consumption-oriented hybrids use fundamentally different approaches. Reducing fuel consumption is an issue in sports cars too. But in a large-scale production vehicle you might replace the 6-cylinder ICE with a smaller 4-cylinder, then add an e-motor so you still have the same overall system performance. Whereas in the Performance sector I’d probably use one or more e-motors to add power to my 8-cylinder engine. The focus is on high performance and agility, not maximum range. And for weight reasons, you’d use a battery that might not have the highest capacity, but provides power quickly through its high power density.

How is growing electrification in large-series applications changing the role of transmissions in general – not just in sports cars?

In the last ten to fifteen years, transmissions have played an increasingly important role. More and more, they’re becoming central torque coordinators in the powertrain. When you have multiple drive sources on board, the transmission is where they converge. Hybrid managers are often located near the transmission – or the functions are combined in the TCU. Actually, the engine now plays a smaller role; the TCU will usually handle its torque.

Looking further ahead, what are the prospects for dedicated transmission concepts, or DHTs?

Our assumption is that DHTs will replace ‘normal’ transmissions in many areas. One reason is that we’re taking mechanical complexity out of the system and replacing it with electrical functions…